Almost all trucks today are powered by diesel engines and fossil fuel. Changing how trucks are powered is essential to solving the problems of air pollution and climate change. After all, trucks account for a substantial share of both pollutant emissions and CO2 emissions on California’s roadways. But what are the feasible strategies and costs for reaching a future with zero- or very-low-emissions trucks?

This question becomes even more challenging when focusing on “long-haul” trucks. Such trucks, typically tractor/trailer Class 8 vehicles weighing up to 33,000 pounds unloaded, can travel 500 miles or more per day, and have some challenging energy requirements—they must be able to carry enough energy, or have rapid access to it, to be able to travel these distances with up to a 40,000-pound payload.

From a regulatory perspective, the California Air Resources Board is in the process of proposing a new truck sales mandate that would require truck manufacturers to sell ZEV trucks, starting in 2024.

How can we power such vehicles with zero emissions? At the Institute of Transportation Studies at UC Davis, we strove to answer this question from a research perspective by looking at four technologies designed to provide power to long-haul trucks while producing zero tailpipe emissions. These technologies are: a catenary system; hydrogen fuel cells; dynamic inductive chargers embedded in the roadway (capable of charging moving trucks); and battery electric vehicles (BEVs). The first three of these are covered in a full report (here) and BEVs will be covered in an upcoming report.

We compared the technologies to each other and to a baseline diesel truck—in terms of technical requirements, current status, challenges, costs, and the potential for future improvements and scale-up. We considered both the vehicles and the energy infrastructure they would need to operate. We modeled a future (maybe 10 years out) where both trucks and infrastructure benefit from economies of scale. For our comparisons, we simulated a situation with 5000 trucks travelling 500 miles of roadway per day (which is a lot). We amortized the vehicle and infrastructure costs over this level of service and over many years (i.e., 20 years to pay off the infrastructure, 5 years for trucks with some resale value).

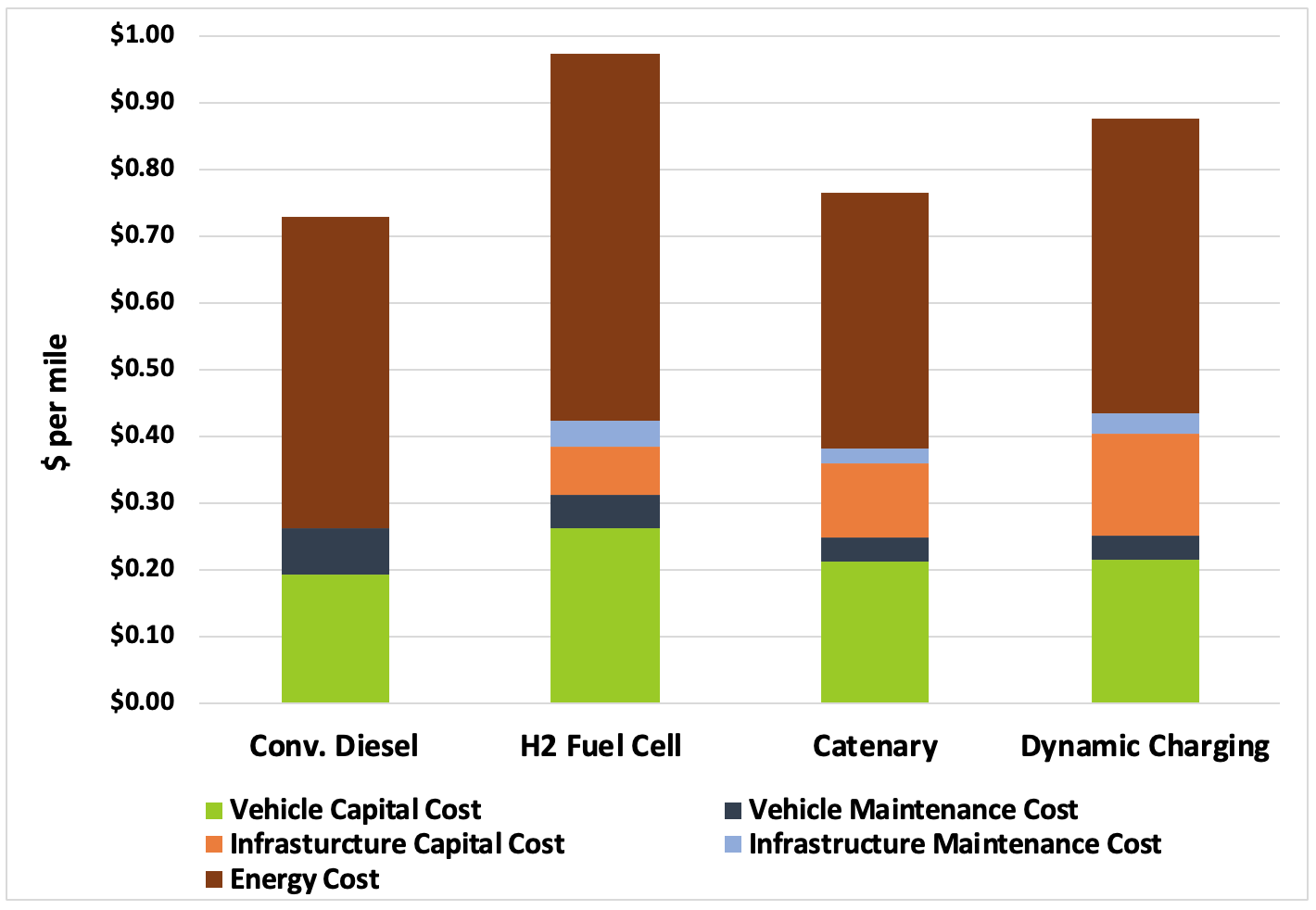

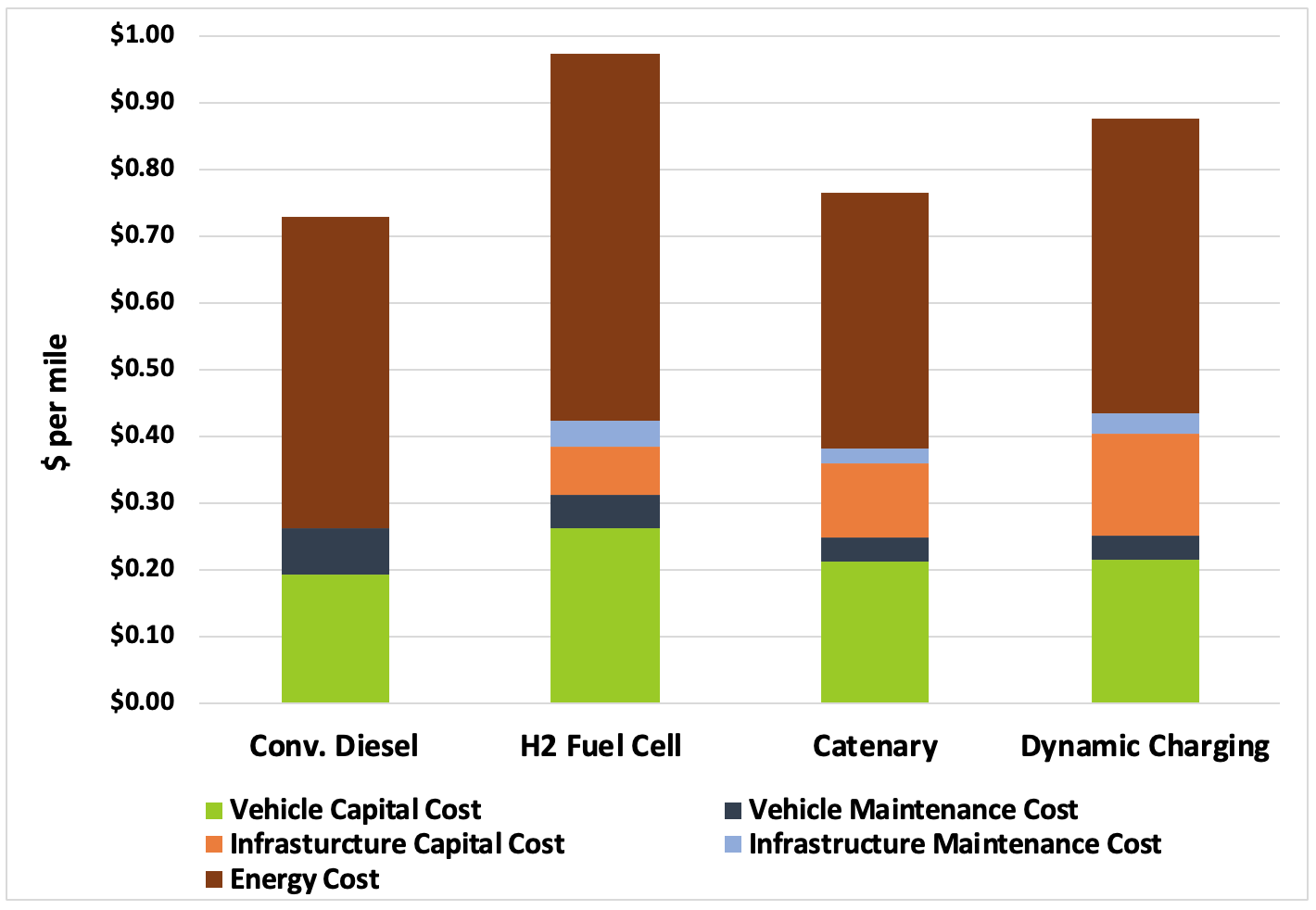

Though there are many factors affecting the comparison, and we consider a range of sensitivity cases, the figure shows our “base case” results: costs per mile for diesel and the first three technologies. The three cleaner technologies are all within 30% of the cost of diesel but none quite match it. The preliminary results for BEVs (not shown), based on slightly different assumptions, indicate that their total costs in a long-haul situation could be on the low side, ranging from $0.45–0.82 per mile versus $0.58 per mile for diesel.

In all cases the range of costs reflects uncertainties in vehicle costs, infrastructure costs, and energy costs. But it’s the energy costs (brown part of bars in the figure) that appear to be the most important and most uncertain. Electricity could run from $0.10 to $0.25 per kWh, depending on the nature of the contracts, whether pricing is closer to retail or wholesale, etc. Future hydrogen costs could vary from about $5 to $8 per kg (when derived from electrolysis), assuming large scale development and access to relatively inexpensive renewable power. The base technology, diesel, has a cost that is highly dependent on oil prices, which could range from $50 to $100/bbl or even higher. High- or low-end assumptions on each of these energy prices leads to a relatively good or poor position relative to the others.

Figure: Relative cost per mile of different technologies based on 500 miles of roadway.

But what exactly are these technologies? What are their advantages and disadvantages?

In the catenary system, overhead wires deliver power through a pantograph with electrical contacts rising off the top of the vehicle. Catenary systems have been widely used for light rail and trolleys, so the technology is well developed. Trials of catenary trucks are underway in Sweden and the Port of Los Angeles. The major challenges would be to install the infrastructure and provide another power source to trucks for when they leave wired roadways.

Dynamic inductive (or “wireless”) charging similarly provides electric power to moving vehicles, from a series of transmitting coils embedded in the roadway. The charge is delivered, with about 90% efficiency, over a short distance to a receiving coil on the bottom of a vehicle. The challenges and costs are like those of the catenary system, but this system would require installation of transmission coils in road beds. Like a catenary system, this system would require the installation of at least hundreds of miles of infrastructure before it would likely be sufficient to attract users—truckers willing to invest in the equipment needed to be compatible. Indeed, this chicken-egg dilemma is a factor for all four technologies: which comes first, investment in infrastructure or vehicles?

Hydrogen fuel cell (HFC) vehicles use hydrogen, as a liquid or compressed gas, to generate electricity from an on-board fuel cell. The hydrogen takes up less volume and weight than do batteries, and refueling is much faster than battery charging. A hydrogen system could also be scaled-up more cheaply and evenly than catenaries or inductive charging. However, infrastructure challenges are considerable in terms of the transportation (or on-site generation) and storage of hydrogen, as refueling stations would have to be 10–30 times larger than diesel stations. Two HFC trucks have been produced, the Vision Tyrano (200-mile range) and Nikola One (800- to 1200-mile range).

Battery electric long-haul trucks typically rely on plugging-in to be recharged (though we do assume some battery electric range for trucks accessing catenaries or dynamic induction systems). Most battery trucks currently have a range of less than 250 miles. The major challenges in applying this technology to long-haul trucks are the large quantity and weight of the required batteries. We estimate that about 1200 kWh would be needed, with a weight of well over 10,000 pounds. This means long recharging times and a potentially large reduction in payload (since battery weight takes away from what could be allocated for goods). In our analysis we assume some reductions in battery weight in the future and access to fast charging, but these two concerns remain.

As long as available electricity is from low carbon sources (namely renewables), the CO2 emissions for catenary, dynamic inductive charging, and BEVs would be low. (The electric grid in California is targeted to be fully renewable by 2040.) The same is true for HFC trucks using electrolytically generated hydrogen, though in the nearer term, the lower efficiency of these trucks (and production of hydrogen) would mean higher CO2 than the pure electric options. CO2 would also be considerably higher if the hydrogen were derived from steam methane reforming of natural gas, which is common today.

In sum, each technology has several advantages and challenges, and there is no obvious winner. From the point of view of infrastructure needs and scale-up, hydrogen may have an advantage. Battery electric trucks provide an attractive option with lower infrastructure costs and potentially lower overall costs but would compromise payloads unless the weight of batteries comes down significantly or compromises are made on range. Finally, catenary and inductive charging systems could work best in areas of dense truck traffic but will need to be extensive enough to work for trucks covering many miles and will require the biggest up-front investments.

Two major questions that need further research are: How do we best manage scaling-up each technology? And how large will public investments and incentives need to be to create a self-sustaining system with adequate infrastructure? The UC Davis STEPS+ Program and Sustainable Freight Research Center will continue to work in this area.

This blog is drawn from a Caltrans “Planning Horizons” educational forum presented by Dr. Fulton this spring. To view a video of his presentation click here and select March 2019. To access the PowerPoint from the presentation click here. To access the full report that this blog and the talk are based on click here.