It’s not just the wind at their back. That bicyclist you saw with a comfortable cadence flying down the road is a part of a new transport trend that’s good for rider health and the environment—the electric assisted bicycle, or e-bike. However, barriers and inequities in e-biking signal a need for new policies to promote bicycling in US cities and make bicycling safe and accessible for all people.

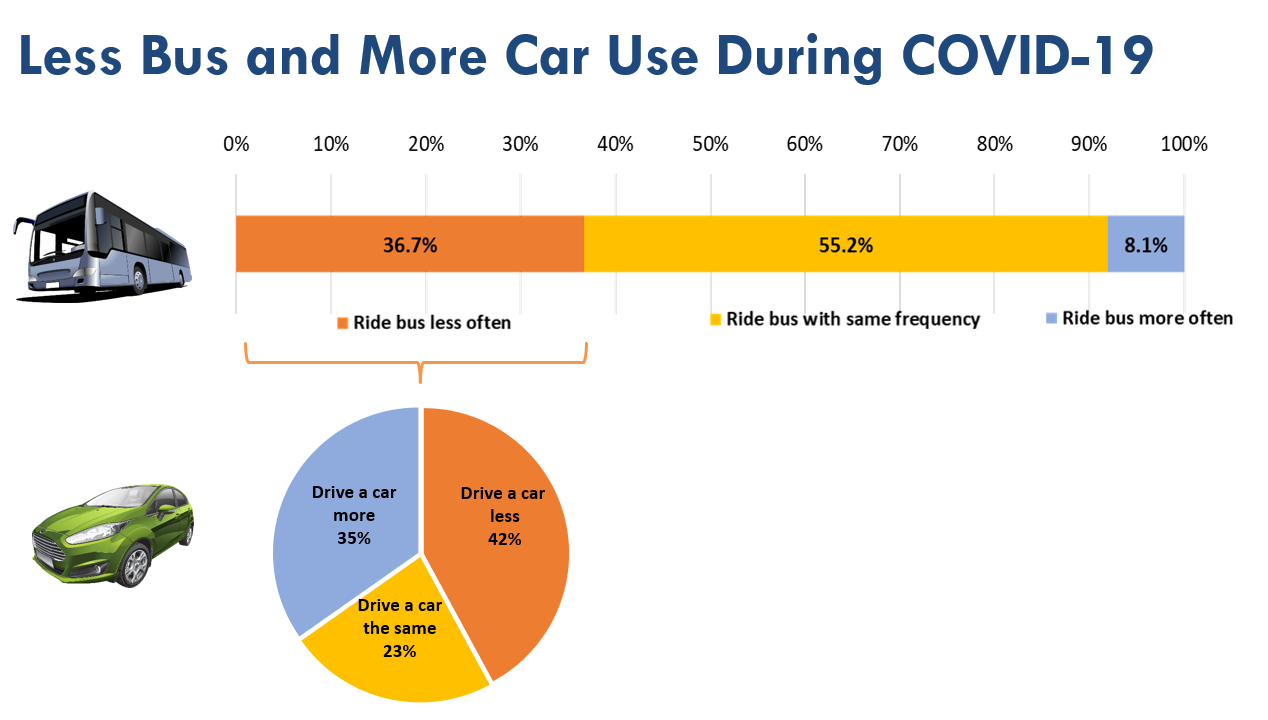

Much has been written in recent months about the increase in bicycle sales due to COVID-19. My colleague, Susan Handy, recently commented on this topic in A COVID Boost for Bicycling. It turns out that US e-bike sales have experienced impressive growth, both before and since the pandemic began, with June 2020 reporting a 190% sales increase over June 2019.

This growth is a good sign for the sustainability of transportation because e-bike use tends to increase bicycling frequency, resulting in greater physical activity (even if intensity is lessened by the electric assist). It also tends to reduce driving and could greatly reduce greenhouse gases if adopted widely.

One of the greatest benefits of e-bikes over conventional bikes is the added distance a bicyclist can ride in a given time. This benefit is greatest in areas where the distances between places of interest are relatively short but perhaps perceived as too long or too arduous for conventional bicycling. And this leads to an important additional aspect of e-bike growth: e-bikes now come in different shapes and sizes, from light folding bikes suitable for commuters to heavier-duty cargo bikes designed for parents to transport groceries and children, or for delivery companies to carry goods.

Here at UC Davis, our early research on e-bicycling pointed to some specific barriers for e-bikes such as fear of theft, perception of cheating, and increased cost. Some of these barriers seem to be decreasing, but many others remain. E-bikes tend to share one of the strongest barriers to conventional bicycling, the lack of safeand comfortable environments to ride in. We found that road environments affect the psychological stress of bicyclists and perceptions of comfort for current and prospective bicyclists. Furthermore, research by our group and others shows that bike lanes and paths that are protected and separated from car traffic are much preferred by current and prospective bicyclists and provide important safety benefits. This evidence indicates that refocusing selected streets away from cars and towards bicycles could help normalize this sustainable travel mode.

In light of policing inequities and the recent experimentation in US cities with open streets to support walking and bicycling during the pandemic, many questions remain as to how to successfully and equitably implement changes that encourage more bicycling. Infrastructure planning that fails to engage with and benefit marginalized communities will continue to make the bicycle a “symbol of gentrification and displacement” instead of a “path to freedom” for those most in need. As highlighted in our last blog by Jesus Barajas, inequities and racism in land use development and the policing of public space, along with specific policies that target low-income, black, and immigrant bicyclists keep safe biking and e-biking unavailable to many. Guidance and recommendations for bike planning and policy by my colleague Sarah McCullough and coauthors demonstrate many additional steps that are needed to make bicycling equitable.

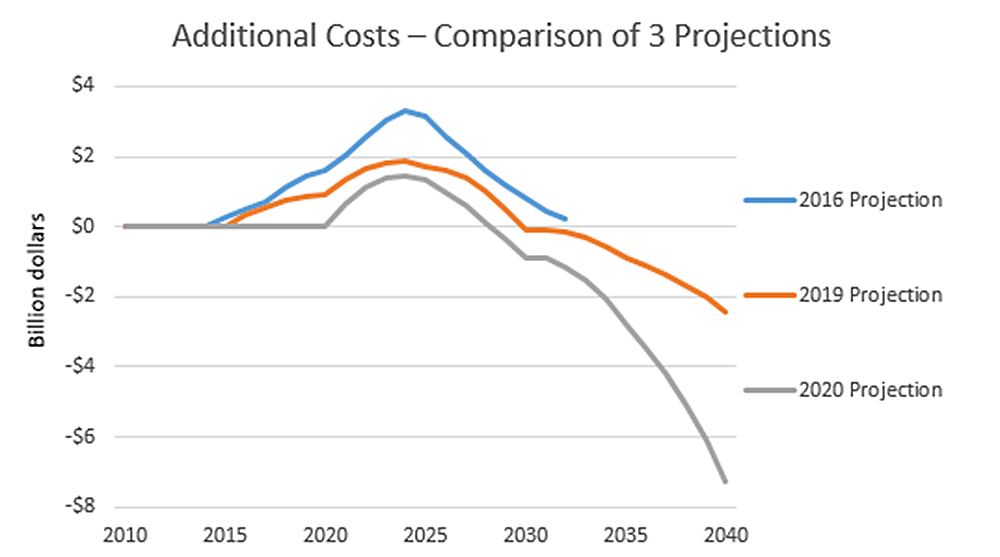

Another equity concern specific to e-bikes is their high cost, which prohibits their adoption by low-income households, who may have the most to gain from this new vehicle. This year, one California bill (AB-2667) attempted to put e-bikes on the Clean Vehicle Rebate Program, giving e-bikes a more equal footing with electric cars. Although this particular bill was unsuccessful, policies in Europe to reduce e-bike costs are widespread and growing, giving policy makers in the US a suite of strategies to try.

Increasing people’s exposure to e-bikes is another key to getting more of them on the road. Our ongoing research suggests that people who have had a chance to ride an e-bike are more likely to consider using one as a primary commuting vehicle. One way to expose more people to e-bikes is through sharing programs. With Lime’s acquisition of Jump bikes and the general shift from dockless bikes to dockless scooters in the micromobility service industry, cities may need to play a more active role in providing e-bike share or leasing services. Indeed, many city-owned docked bike shares in places like Portland, Toronto, and Chattanooga are now transitioning to e-bikes. These places will offer a great natural experiment on the general influence of shared e-bikes on e-bike buying and use.

With the COVID pandemic likely to last many more months, the time is right for targeted and equitable investment in e-bicycling as a physically-distanced and sustainable mode of travel that should be safe and available to all. The current growth in demand for e-bikes should be seen to reflect a public enthusiasm for more bicycling-friendly infrastructure, policies, and services in US cities.

—

Dillon Fitch is Co-Director of the BicyclingPlus Research Collaborative at ITS-Davis. He studies travel behavior and transportation planning and develops tools to improve planning for bicyclesand emerging small vehicles.