By Lew Fulton and Mike Sintetos

Much has been written about the three revolutions transforming transportation—automation, electrification, and sharing—and about their potential to shape the future sustainability of the transportation system. Yet it is also important to consider that these profound changes in travel options may also have varying impacts on the environment.

Take, for example, the potential of vehicle automation. Fully automated vehicles may become widely available as a low-cost ride-hailing or private vehicle option within a decade. The lower monetary and time-cost (related to time spent traveling) of automated vehicle travel could dramatically increase vehicle miles traveled, pollution, and traffic congestion, unless policies are put in place to manage a rapidly changing system. Low-cost, driverless ride-hailing trips may also reduce the incentive to pool rides if it reduces the price advantage of pooling. Furthermore, whether the vehicles are electric or gas-powered will be a critical determinant of their environmental impacts.

The relative costs of mode choices, technology choices, and new technology introductions will be a major factor in whether the net effects of these “3 revolutions” add up to more or less traffic, pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. Fundamental questions to consider include: will future travelers decide to purchase their own automated vehicles or use automated ride-hailing? Will they use fleets of “robo-taxis” primarily for solo trips or will they share those trips with others, reducing traffic impacts? Will they choose electric over gas-powered vehicles in cases where they have a choice? And what factors will go into these decisions?

We have explored these questions in a series of recent papers.

Factors Influencing Travel Choice

Our research explores the many monetary and non-monetary factors that go into people’s travel decisions. Monetary costs related to owning a vehicle include the purchase cost, maintenance, fuel, and parking costs. Among these, some are fixed and some vary, occurring with each trip. The variable costs appear likely to be more influential in short-term decisions about what modes to choose for a given trip (once a car is bought, the purchase cost may be ignored in daily travel decisions). For travel choices such as on-demand ride hailing, all costs are essentially variable, paid for each trip and roughly per mile.

Non-monetary factors also play a big role in traveler mode choices. Travel time, convenience, certainty of departure and arrival times, safety/security concerns, and other factors all play a role in our decisions about how we get from point A to point B. There is considerable research exploring these factors in traditional mode choice contexts, such as driving vs. taking public transit. But it is less clear how these factors will impact choices in our “3 revolutions” future, with its many new types of choices. Which travel choices will appear to be lowest cost in different situations when considering monetary and non-monetary costs together as a “generalized cost”?

To understand how people might make travel decisions in a future with fully automated vehicles, various ride-hailing and sharing options, and the possibility of vehicle electrification, we need to understand the relative values of these different monetary and non-monetary factors and how these generalized costs might compare across travel modes.

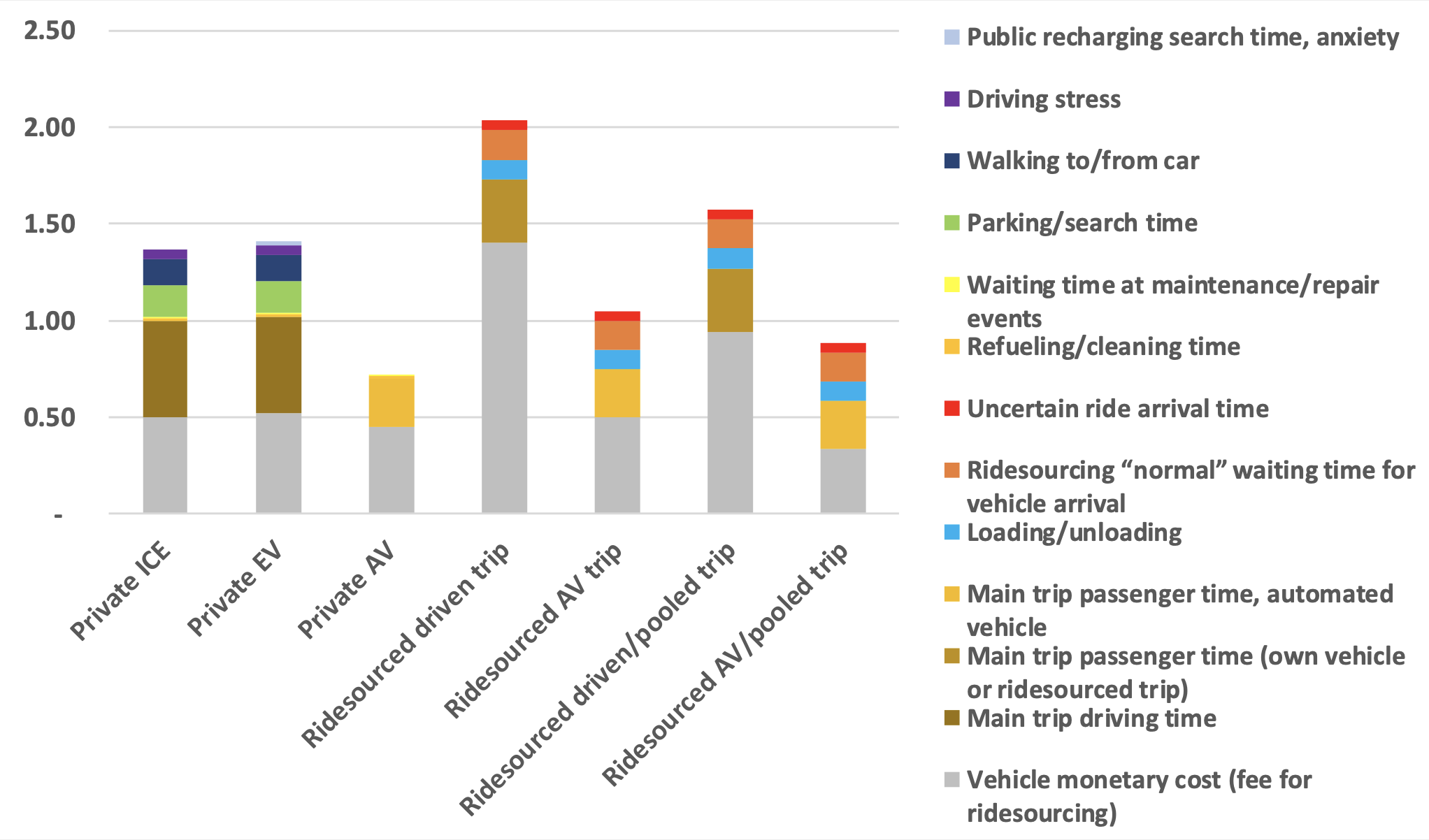

Our team used existing research and data estimates, along with some projections of future costs, to develop generalized cost estimates for several future travel modes, including private vehicle travel, solo ride-hailing, and pooled ride-hailing, for electric and gas-powered vehicle technologies, considering the presence of a human driver in the near term analysis and focused on automated vehicles in the 2030-35 timeframe. Our estimates take into account the costs of vehicles, energy, and perhaps most importantly, the value of time during specific trips. We looked at several specific trip situations, focusing mainly on 1) a short-distance, urban trip, and 2) a longer-distance, suburban trip.

Generalized Costs of Future Travel

While we have estimated monetary and some non-monetary costs of travel options, we have ultimately learned that there are many more possible costs than we can realistically estimate values for at this time. One example is the “cost” associated with the hassle of having to remove personal belongings such as child seats from a shared vehicle rather than leaving things in a personal car. We used value of time assumptions to estimate values for a number of factors that have a clear time component, such as the time spent traveling in the vehicle, waiting for a vehicle to arrive, and searching for parking.

Overall, our findings suggest that a few things are likely to occur once automated vehicles are widely available. These are reflected in the figure below, which provides a snapshot of relative costs of modes in 2030 taking into account a range of monetary and non-monetary factors:

- Not having to drive will save about half the generalized cost of private vehicle trips, as long as people find their time as a passenger somewhat useful and preferable to driving.

- A driverless ride-hailing trip appears likely to be, from a generalized cost point of view, cheaper than today’s ride-hailing options, including pooled trips, with no need to pay a driver.

- The reduced monetary cost of both solo and pooled ride-hailing services will shrink pooled ride-hailing’s relative advantage without affecting its non-monetary disadvantages (longer travel time, less predictability, potential safety concerns). Thus, pooled ride-hailing may become even more unappealing in an automated future.

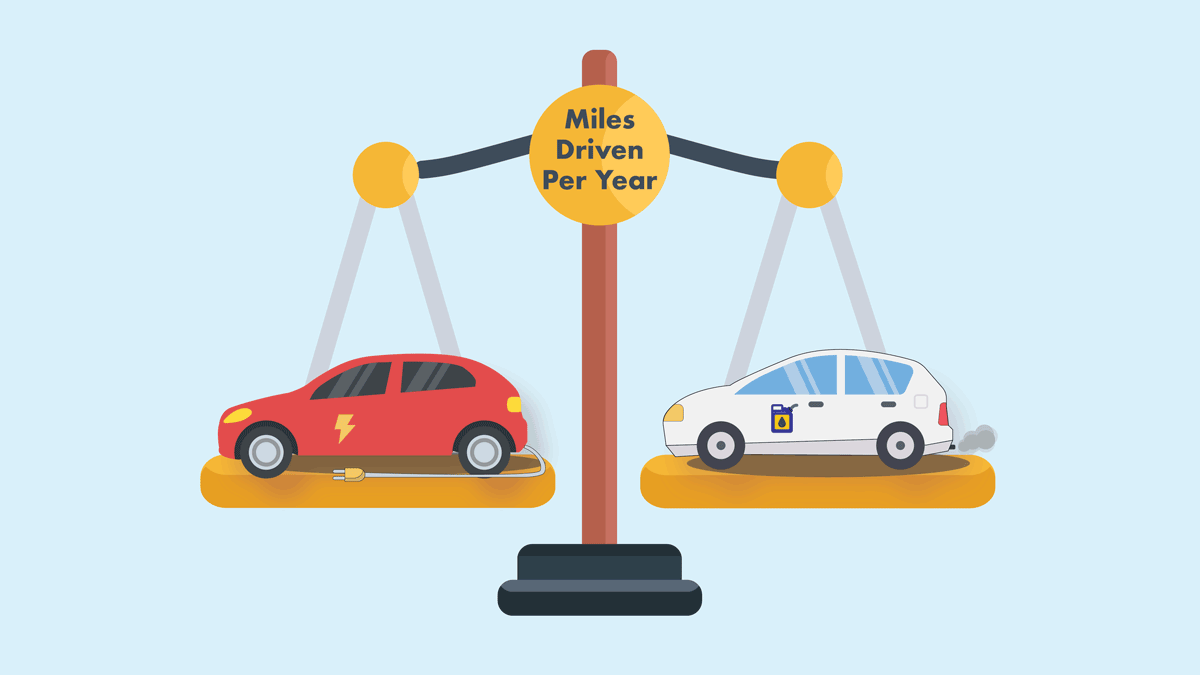

- While electric vehicles are slightly more expensive (higher purchase cost, mostly offset by lower driving cost), their relative cost differences with conventional vehicles are tiny compared to the various non-monetary costs associated with different modes. Once automation is available, it seems the financial cost of whether a vehicle is electric or not will be relatively unimportant compared to automation-related factors.

Figure 1. Monetary and non-monetary costs in 2030 for various vehicle types, for a typical mid-length trip (US dollars/mile) (Source: Estimating the Costs of New Mobility Travel Options: Monetary and Non-Monetary Factors)

All of these costs will vary by situation, by person, and over time as these technologies develop, and while we explore these uncertainties in our papers, we acknowledge that much more work is needed to investigate the range of potential costs. Still, we believe these basic results are likely to hold up across many situations. If one had hoped that the net costs of various trip choices would eventually push people to share rides and reduce vehicle miles traveled, these initial results are not encouraging.

Balancing the Scales

Policies such as pricing strategies (e.g. road tolls and urban access pricing schemes) can tip the balance of costs between modes. In our May 2021 Transport Policy paper, we looked at existing road pricing schemes around the world to understand whether trip fees on solo ride-hailing, per-mile tolls, or congestion-area fees would change the relative attractiveness of solo private vehicle driving vs. ride-hailing. Our analysis showed that, with the exception of London’s daily charge to enter the central city, none of the existing road fee systems create differences that are anywhere near large enough to significantly affect travel choices. These policies tend to create differences (e.g. between solo and shared trips) that are less than $0.10 per mile, while we estimated the generalized cost differences between these modes to be as high as $1.00 per mile.

Therefore, future road pricing policies may need be much more aggressive in terms of creating per-mile cost differentials in order to have considerable impact on overall car travel, ride sharing levels, and shifts away from automobile travel altogether. Without such policies, the low cost of travel in either private or on-demand automated vehicles could lead to even more vehicle travel and roads clogged with single-passenger automated vehicles. One silver lining from our research points to the fact that the relative closeness of the generalized costs of electric vehicles and conventional vehicles may provide a good opportunity to use road pricing to promote electric vehicle adoption—a definite benefit for environmental concerns.

Based on this work, we believe that governments looking to increase the use of pooled ride-hailing to encourage more sustainable travel choices can take several actions:

- Set ride-hailing fees to meaningfully incentivize pooled travel. Fees on solo trips need to be much higher to make a difference.

- Prioritize access for pooled travel. Policies that reduce travel times for pooled vehicles, such as curb access or priority lanes, will lower the generalized costs of these modes.

- Consider per-mile fees or restrictions on personal automated vehicles. The time is now to implement these policies, before AVs are widespread.

If left to develop unregulated, automated vehicle technology may only reinforce our tendency towards solo travel, particularly private automated vehicle travel, and encourage much longer trips, given their lower generalized cost. Early and effective policy action will be needed to avoid this path and ensure a more sustainable transportation future.

Additional Resources

January 2020 Transport Policy paper

May 2021 Transport Policy paper

SB1 Report

NCST Report

Policy Brief

—

Lew Fulton is Director of the Sustainable Freight Research Center and the Energy Futures Research Program at the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies.

Mike Sintetos is Policy Director for the National Center for Sustainable Transportation (NCST) and SB1 Research Program at the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies.