Is net zero-carbon energy really attainable for the entire US? If so, when? A major new study of deep decarbonization of the US economy, entitled the Zero Carbon Action Plan, was published October 27. It was conducted by senior academics and other thought leaders, working under the auspices of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, an initiative of the United Nations. The authors developed scenarios for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, analyzed different strategies, and recommended policies and investment actions. We served as the lead authors of the transportation section of the Plan and presented a webinar with our coauthors on that section, on October 29.

Is net-zero carbon possible for transportation? Our answer is a qualified yes: achieving close to net-zero carbon emissions is possible by 2050, but it will require extraordinary focus and commitment. The No. 1 strategy for transportation, dwarfing all others, is definitive: electrify nearly all cars, trucks, and buses while transitioning the electricity sector to zero-emission energy. All other strategies pale in comparison.

Electrifying light duty vehicles—cars, pickups, and SUVS—means having them be battery electric vehicles, plug-in hybrid vehicles, or fuel-cell electric vehicles. Battery electric vehicles run exclusively on rechargeable batteries; plug-in hybrid vehicles add to this a small internal combustion engine that is gasoline powered and supplements the battery power; and fuel cell electric vehicles run on liquid hydrogen that is converted to electricity on board. We consider all of these to be “electric” and are not taking a position on what share each of these technologies should have, other than they must add to 100% of vehicle sales by 2040 to achieve the carbon target.

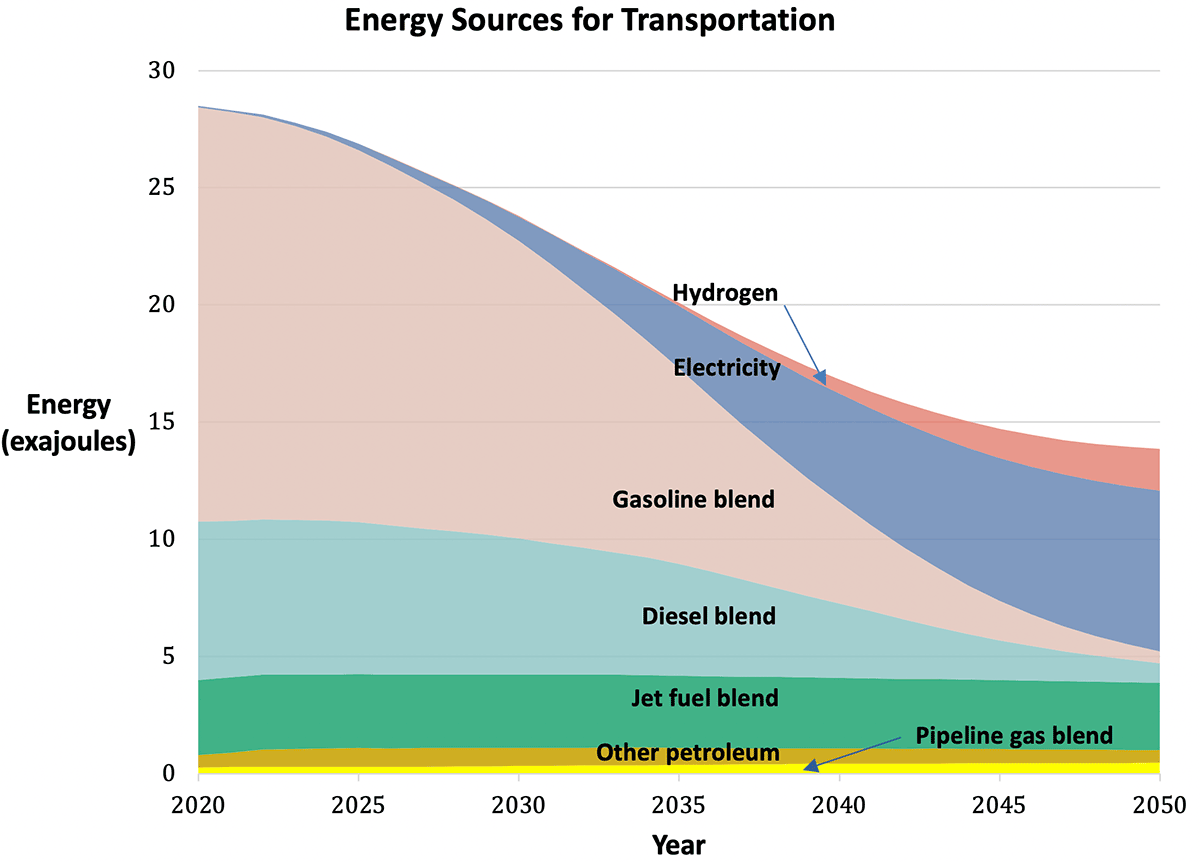

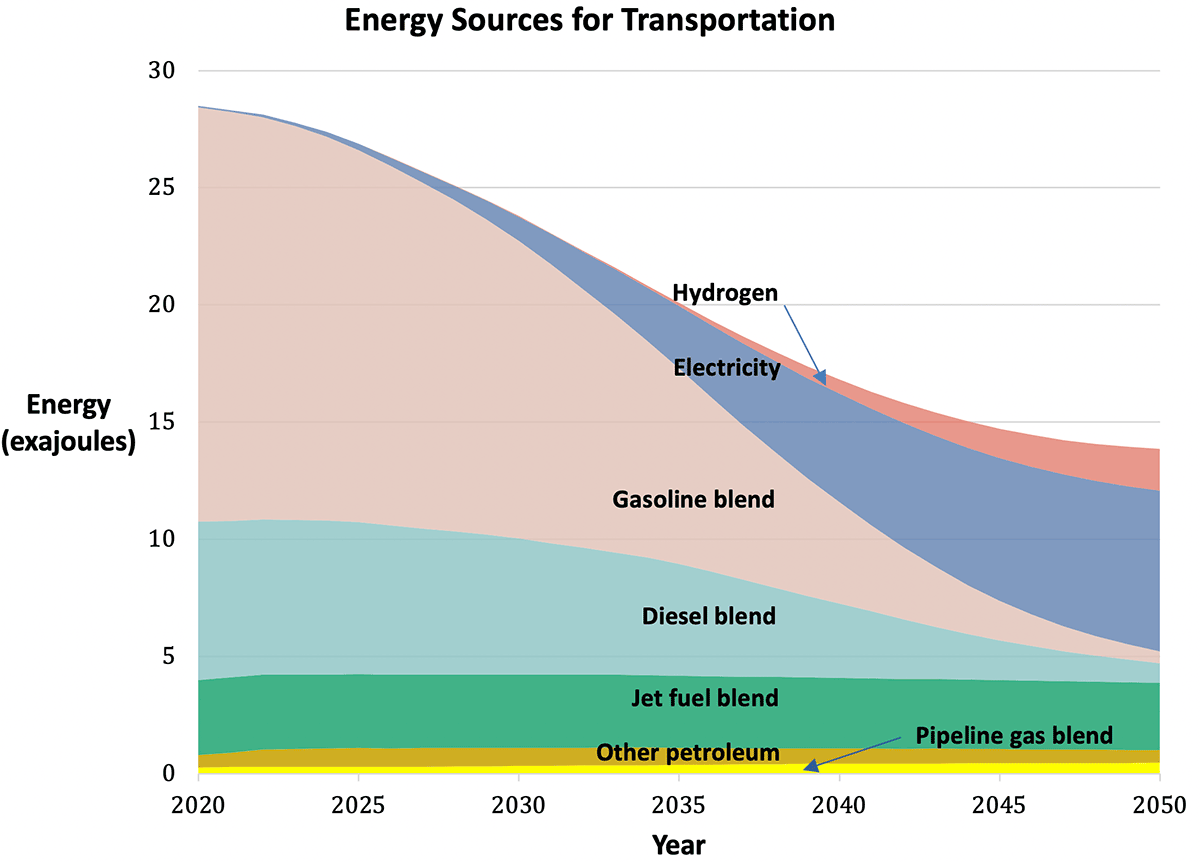

To achieve deep decarbonization, most larger trucks, from delivery vans to trash trucks and large tractor trailers, would also be electrified, with the energy coming primarily from batteries or hydrogen. Some long-haul trucks would likely use low-carbon biofuels or electricity-derived liquid fuels, as well as hydrogen. Achieving net-zero carbon emissions will require the use of renewable energy to produce electricity and hydrogen and a transition to lower-carbon and more sustainable biofuels.

Changes in the sources of energy for transportation that would achieve a nearly 100% reduction in domestic transportation greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Note, the energy source that most increases is electricity and most decreases is gasoline blend. Blends would have increasing shares of low-carbon biofuels or electrofuels (from Zero Carbon Action Plan).

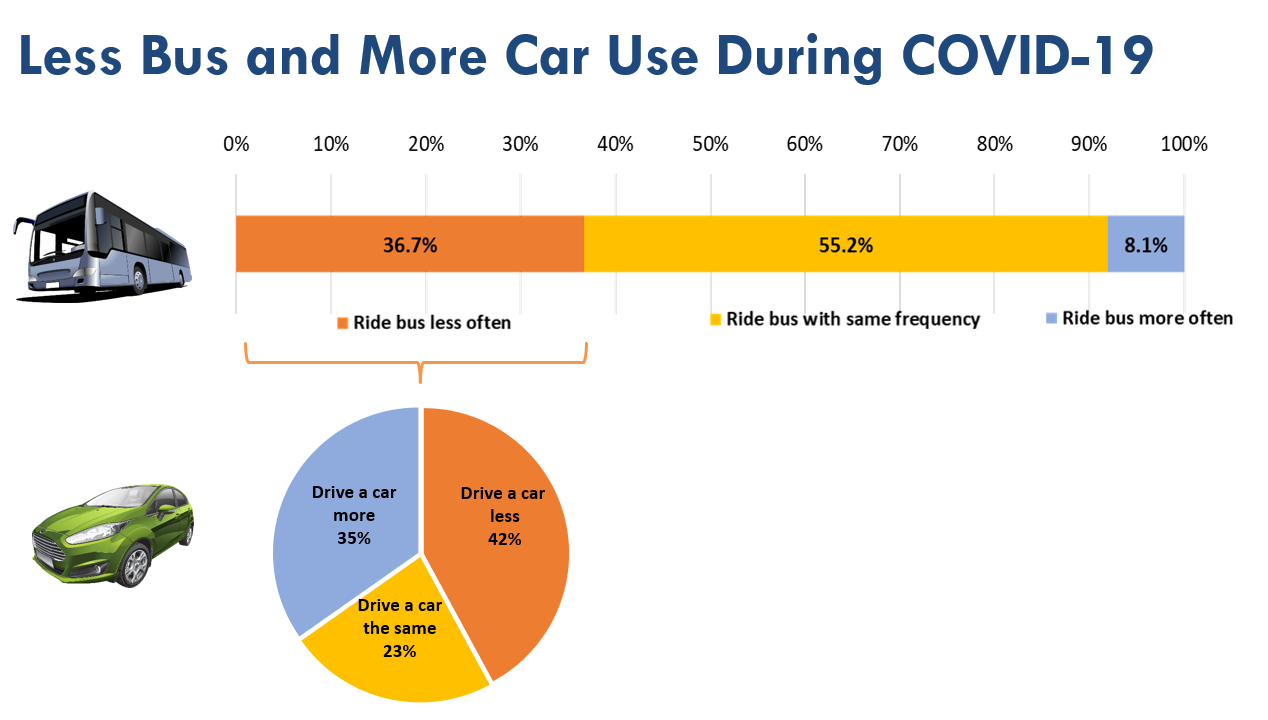

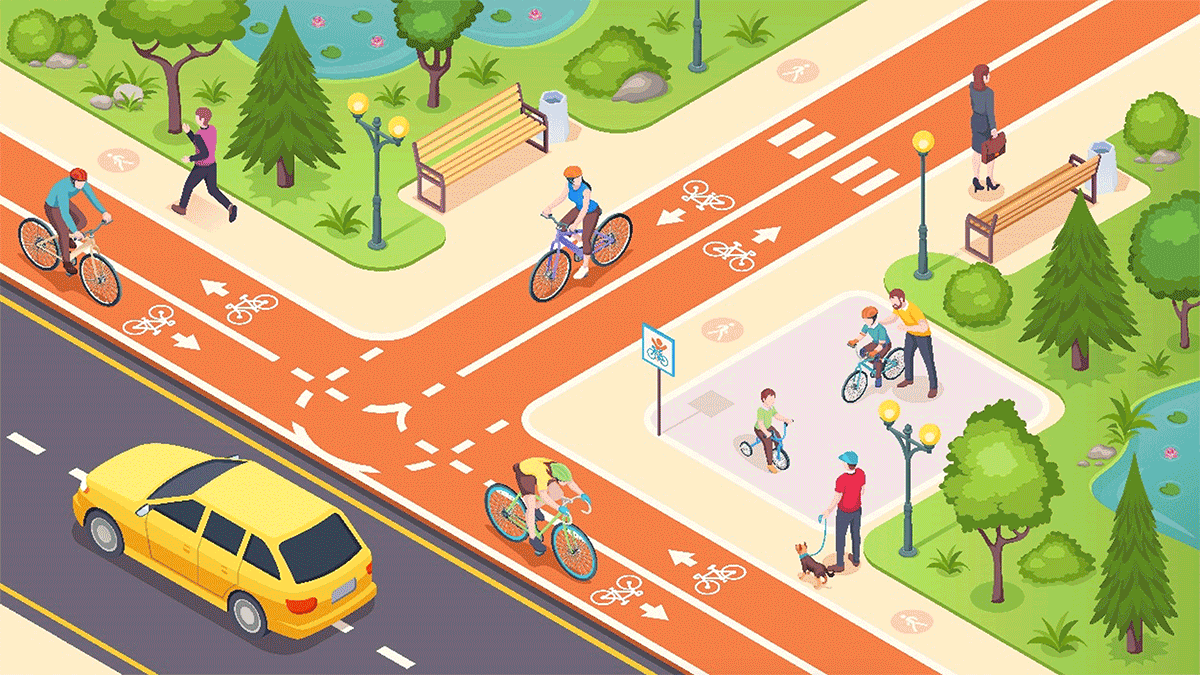

Another important strategy is reducing vehicle use by providing greater access to alternative modes of transportation, including transit and active modes such as biking and walking. In addition to the greenhouse gas reduction benefits, reductions in vehicle use would generate massive co-benefits: less space and cost for roads and parking, less wasted time in traffic, fewer traffic fatalities, more livable communities, and improved public health. However, these co-benefits are only realized if we devise other means of providing mobility and accessibility to jobs, health care, school, and more, especially for those who are mobility disadvantaged, whether for reasons of physical or economic limitations. Thus, this vehicle use strategy must be accompanied by investments and policy to support walking and biking, transit, and demand-responsive ride-hailing—with a focus on providing more mobility at less cost. The strategy of reducing vehicle use is compelling because of the large co-benefits, but the challenge of changing behavior is daunting. Based on research by ourselves and others, we settled on a goal of 25% reduction in vehicle use by 2050, acknowledging that electrification of vehicles will achieve far greater greenhouse gas reductions by then.

Infrastructure to increase active modes of transportation.

Other strategies are also important, including for planes and ships, which account for just over 10% of transport-related greenhouse gas emissions. A different set of investments and policies are needed, such as supporting research and investment in low-carbon fuels and new vehicle technologies like electric airplanes and ferries, and shifting to rail and other less-carbon intensive options.

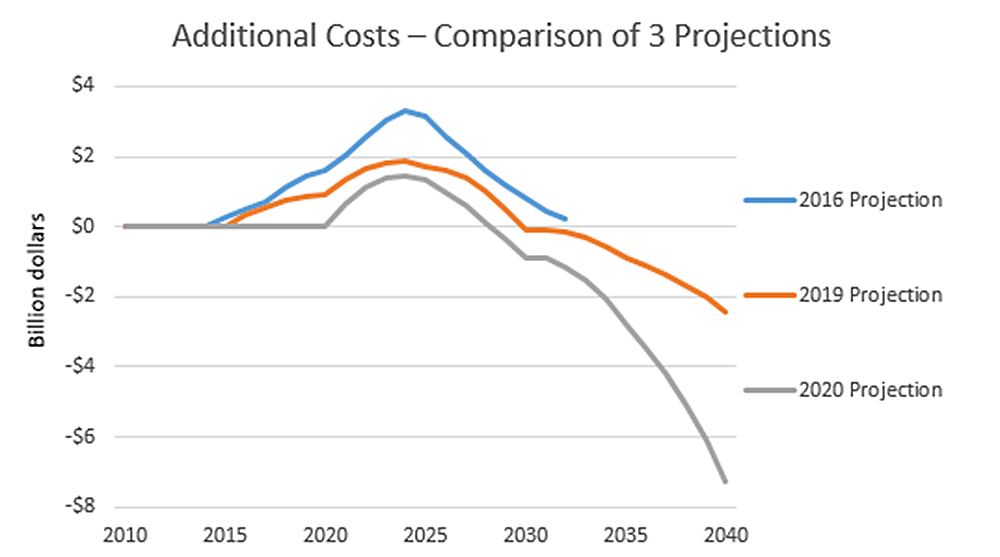

All of this is possible within the coming decades. Indeed, virtually all analyses indicate that this transition is good not only for the environment, but also for the economy. Costs are declining so fast and so far for batteries and renewable energy, that if we scale up quickly, the total cost of owning and operating most cars, trucks, and buses—all but the large trucks used for long distance freight shipments—will be cost competitive with gasoline and diesel vehicles by about 2030 and in some applications, much sooner. And soon after that, the net effect will be savings relative to gasoline and diesel cars and trucks. In other words, we will be coming out ahead economically with battery and hydrogen vehicles within 10-15 years!

While the economics of this transition are compelling, it doesn’t mean it will be easy. Survey research finds that consumers remain uninformed about electric and fuel cell vehicles, and that they don’t make vehicle purchase decisions based on an analysis of the “total cost of ownership” over the vehicle lifetime. Even when they do, they tend to underestimate how long they would keep the vehicle, what the future revenues from selling their vehicle into the second-hand market will be, what the future price of fuels will be, and much more. Moreover, cost comparisons of electric vs. gasoline and diesel vehicles do not address other consumer concerns, including those associated with “range anxiety.” Those living in apartment buildings may be apprehensive about where to charge, unless provisions are made for public charging to overcome their concerns. And those who travel regularly to rural areas will likely be frustrated by limited fueling opportunities. Others will experience unfavorable economics if they do not drive much, since the lower energy and maintenance costs of electric vehicles would be swamped by the higher vehicle purchase price.

Therefore, incentives will be needed to encourage the transition. But the cost of these incentives need not fall on taxpayers. Various policies are possible, already in existence in the US and Europe, to shift the costs to buyers of internal combustion engine vehicles and suppliers of fossil energy. For example, the low carbon fuel standards in Oregon and California set a carbon intensity performance standard for fuel suppliers. Those that cannot or won’t sell low-carbon fuels, buy credits from those that do. These credits translate into incentives to electric vehicle users, paying for nearly the entire cost of the electricity in the case of truck fleets, or consumer rebates of about $1500 for electric vehicle buyers.

Likewise, “feebates” in France and other European countries charge a fee for buying gas guzzlers that is used to fund rebates of up to $10,000 to buyers of electric vehicles—for trucks as well as cars. This policy could be adopted in the US. Along with the low carbon fuel standard, these policies would generate more than enough incentive funding to convince most consumers to buy electric cars and trucks—with no cost to taxpayers.

Just as some of the largest benefits from reducing vehicle use go well beyond climate change mitigation, likewise switching to electric vehicles—including school and transit buses—results in significant air quality and public health benefits, especially in communities of color and low-income communities overburdened by pollution.

In summary, the transition to a low-carbon future is already underway and can be expedited with minimal costs to taxpayers and large benefits to consumers, the economy, and public health. It won’t be easy, and some changes will be disruptive, but these changes are necessary to achieve climate and other goals. This transition will require a variety of actions by federal, state, and local governments as spelled out in detail in the Zero Carbon Action Plan report, with policy recommendations summarized briefly below.

Summary of Policy Recommendations

- Rapidly increase the sales of zero emission vehicles (ZEVs) by implementing the following:

- National ZEV sales requirements for cars

- National ZEV sales and fleet purchase requirements for trucks

- Incentives for ZEV vehicle purchases and ZEV infrastructure

- Tighten fuel economy/GHG standards for all new cars and trucks

- Adopt national low-carbon fuel standard covering all fuels for road vehicles and airplanes

- Reduce dependence on automobile travel while increasing access for walking, bicycling, new micro mobility modes, telecommunications, transit, pooled ride-hailing services, and other low carbon choices, especially for disadvantaged travelers, by:

- Shifting federal transportation or stimulus funding from new highway capacity and lane expansions to: bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure and new micro mobility modes; transit in dense areas; and public-private partnerships between transit operators and ride-hailing providers.

- Supporting local and state actions that increase low-carbon travel and investments, reduce single-occupant vehicle use, and increase transit-oriented development.

- Reforming fuel taxes and other vehicle-related fees and adopting pricing policies to favor the use of more sustainable travel options and generate funding for low-carbon vehicle and travel choices.

- Support low-carbon biofuels and electrofuels for aviation, ships, and long haul trucks.

- Support local policies that increase the use of automation for electric, pooled vehicles to reduce vehicle use, provide low-cost accessibility to mobility-disadvantaged travelers, reduce the cost of travel to individuals and society, and sharply reduce the amount of land devoted to transportation.

—

Daniel Sperling is Founding Director of the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies, and distinguished Blue Planet Prize Professor of Engineering and Environmental Policy. He also serves on the California Air Resources Board, overseeing policies and regulations on climate change, low carbon fuels and vehicles, and sustainable cities.

Lew Fulton is Director of the Sustainable Freight Research Center and the Energy Futures Research Program at the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies. He helps lead a range of research activities around new vehicle technologies and new fuels, and how these can gain rapid acceptance in the market.

Vicki Arroyo is Executive Director of the Georgetown Climate Center based at Georgetown University Law Center, where she is also a Professor from Practice. Professor Arroyo oversees the Georgetown Climate Center’s work at the nexus of climate and energy policy. She is also a member of the faculty steering committee for the Georgetown Environment Initiative, a cross-campus effort to advance the interdisciplinary study of the environment in relation to society, scientific understanding, and sound policy.

CATARC Vice President Wu Zhixin spoke at the kick-off meeting

CATARC Vice President Wu Zhixin spoke at the kick-off meeting